Empirically Testing the Boundaries of the Frequency Principle

Xu (2019) and Rahaman (2019) propose that deep neural networks often fit target functions from low to high frequencies during the training process. To what extent does this principle hold?

See my github repo for more details!

Introduction

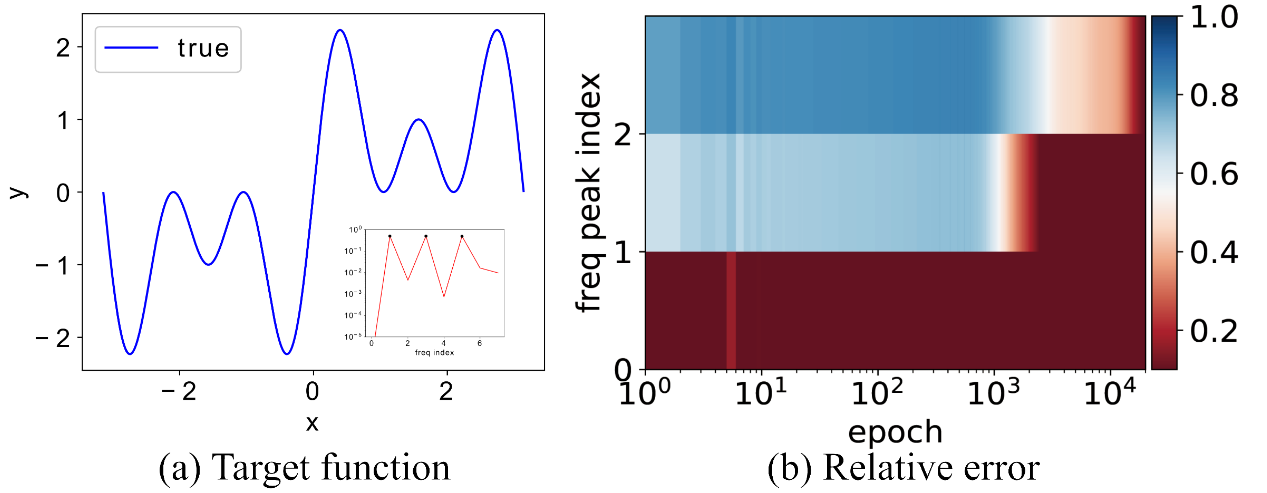

Deep neural networks often fit target functions from low to high frequencies during the training process. Two concurrent and independent works, Xu et al. (2019) and Rahaman et al. (2019), observed and proved this phenomenon, naming it as Frequency Principle and Spectral Bias, respectively. Below is an illustration of frequency principle from Xu (2020): If we use a neural network $h(t)$ to fit the target function $f(x) = \sin(x) + \sin(3x) + \sin(5x)$, using Fourier Transform to decompose both $f$ and $h(t)$ into frequency spectrum and tracking the relative error with respect to the different frequencies, we will find that errors corresponding to lower frequency drop faster.

This mechanism is rigorously proved for DNNs of general settings (any commonly used activation function, general population density of data, a general class of loss functions) in a subsequent work (Luo et al., 2019). The connection between Frequency Principle of over-parameterized two-layer Relu MLP and NTK was further built. (Cao et al., 2020)

The concept of Frequency Principle is appealing because it is strongly related to generalization of DNNs: The lower frequency components of trained networks are more robust to random parameter perturbations (Rahaman et al. 2019), and according to Frequency Principle, among all the functions that can fit the training data, a DNN is implicitly biased during the training towards a function with more power at low frequencies. (Xu et al. 2019) However, several questions cannot be well answered by existing theories and empirical results:

- Although Frequency Principle is proved in a generalized setting, several assumptions are made on the loss function/data distribution/activation function. (Luo et al., 2019) Most importantly, the widely used Cross Entropy Loss does not meet their assumptions.

- Existing experiments for verifying Frequency Principle are mostly on image classification tasks, and few of them are on text-based tasks, e.g., next-token prediction.

- It is unclear whether similar experiments could be extended to Transformers.

Therefore, it is natural to ask: To what extent does Frequency Principle hold? Is it a property of MLPs (under restricted settings), or whether it could be extended to a wider range of training settings, model architectures, and real-life tasks?

The aim of this project is to empirically test the boundaries of Frequency Principle. Experiments are structured into three progressive stages:

- Based on Cao et al. (2020), I verify the theoretical connection between NTK and Frequency Principle, and find that under lazy training regime, Frequency Principle could be fully predicted by NTK theory. I also extend the analyses from ideal uniform distribution to non-uniform distributions and even feature learning regime, where the connection between NTK and Frequency Principle is broken, but Frequency Principle still holds.

- I validate Frequency Principle on 4-gram next-prediction task on MLP, with pre-trained embedding.

- I conduct 4-gram next-prediction experiments on GPT-2.

In this post, I will focus on the key findings from the latter stages of the project (Stage 2 and 3). For a deeper dive into the theoretical framework and implementation details, please check out the github repo.

Methodology: How to Measure Frequency in High Dimensions?

To verify the Frequency Principle, we need to decompose the network’s error into different frequency components. For 1D or 2D synthetic data, we can simply use the Fast Fourier Transform (FFT) or Non-Uniform FFT (NUFFT).

However, real-world tasks involve high-dimensional inputs. In high-dimensional spaces, standard Fourier transforms become computationally impossible. To address this, Xu (2020) proposes two methods: the Projection Method and the Filtering Method. Here, I mainly used the latter.

The core idea relies on the Convolution Theorem: applying a low-pass filter in the frequency domain is equivalent to performing a convolution in the spatial domain, so we could approximate a low-pass filter by convolution.

- Ideally, we apply a low-pass filter $\hat{G}_{\sigma(\omega)}$ in the frequency domain: $\hat{f}_{\text{low}, \sigma} = \hat{f} \cdot \hat{G}_\sigma$.

- We choose a Gaussian kernel, as its inverse is also a Gaussian kernel, then the low-frquency component would be: $f_{\text{low},\delta}(x) = \mathcal{F}^{-1}{\hat{f}(\omega) \cdot \hat{G}_{\sigma(\omega)}} = (f * G_\delta)(x)$

- The $\delta$ acts as the “bandwidth”: a large $\delta$ (wide kernel) results in strong smoothing and extracts global, low-frequency components, while a small $\delta$ retains high-frequency details.

This convolution is defined by the integral: \(f_{\text{low},\delta}(x) = \int f(x') G_\delta(x - x') dx'\)

However, we do not have the continuous function $f(x)$, but only a discrete set of $N$ samples, ${(x_i, y_i)}_{i=1}^N$, where $y_i = f(x_i)$. We approximate the convolution integral at a point $x_i$ using a discrete, normalized summation over all data points:

\[y_{\text{low}, \delta}(x_i) \approx \frac{\sum_{j=1}^N y_j G_\delta(x_i - x_j)}{\sum_{j=1}^N G_\delta(x_i - x_j)}.\]The exact form of Gaussian kernel is $G_\delta(x_i - x_j) = \exp\left(-\frac{||x_i - x_j||^2}{2\delta^2}\right),$ where the denominator $C_i = \sum_j G_\delta(x_i - x_j)$ is a normalization factor.

Finally, the high-frequency component is simply the residual: \(y_{\text{high}, \delta}(x_i) = y_i - y_{\text{low}, \delta}(x_i).\)

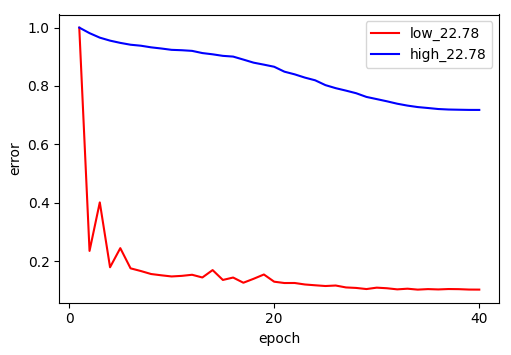

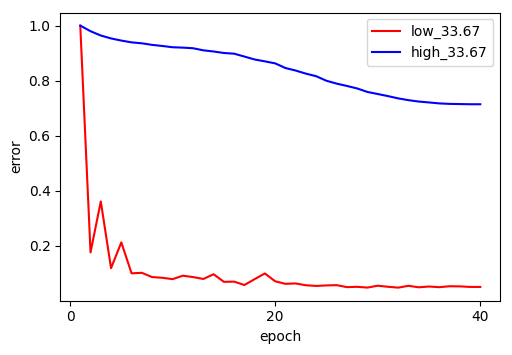

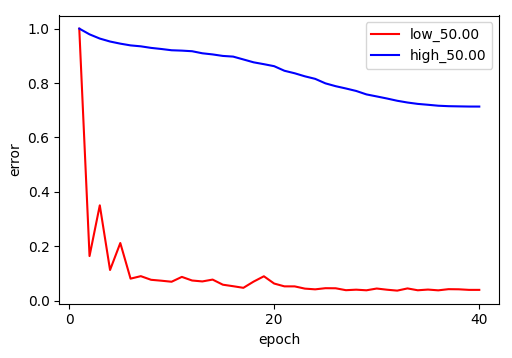

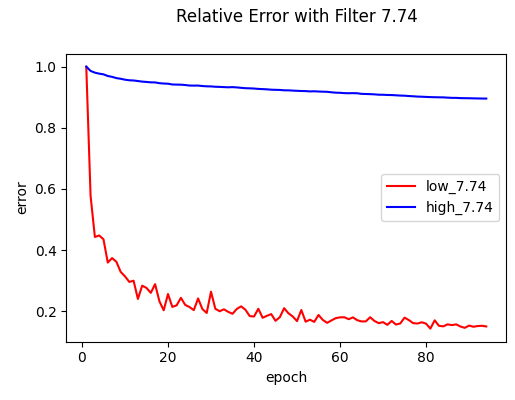

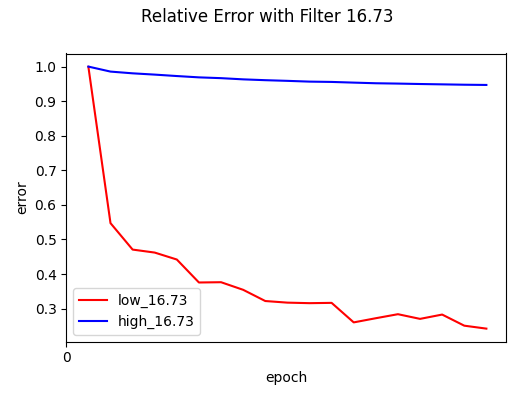

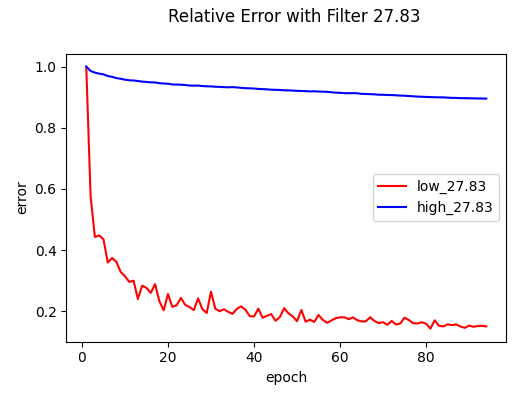

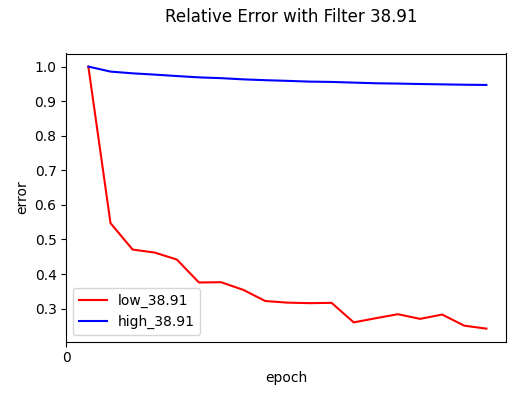

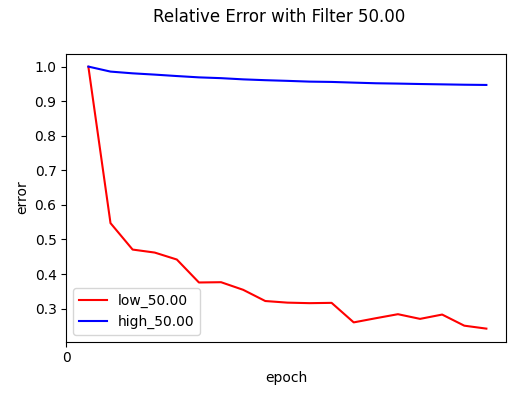

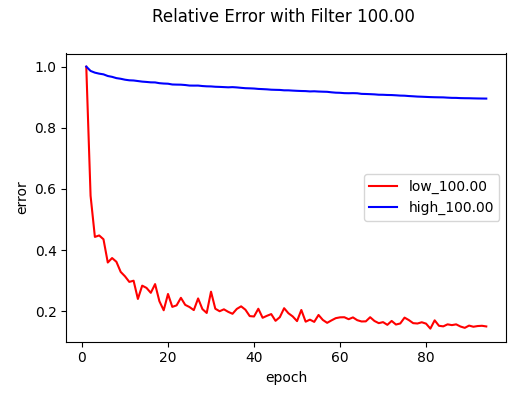

The F-Principle is then verified by showing that the network’s error on the $y_{\text{low}}$ components converges much faster than the error on the $y_{\text{high}}$ components, across a series of $\delta$. Specifically,

\[e_{\text{low}}(t, \delta) = \frac{\|\|f_{\text{low},\delta} - h_{\text{low},\delta}(t)\|\|_{F}}{\|\|f_{\text{low},\delta}\|\|_{F}}, \quad e_{\text{high}}(t, \delta) = \frac{\|\|f_{\text{high},\delta} - h_{\text{high},\delta}(t)\|\|_{F}}{\|\|f_{\text{high},\delta}\|\|_{F}}\]Experiments: Spectral Bias in Language Modeling

Testing this on NLP tasks introduces a computational challenge: the Filtering Method requires computing a pairwise distance matrix between all training samples, which is $O(N^2)$ complexity. With millions of training examples, this is intractable. To overcome this, I employed a Monte Carlo approximation: I sampled a representative subset of $N_{\text{sample}} = 5,000$ points to construct the distance matrix and kernels. During training (on the full dataset), I tracked the spectral dynamics by evaluating the model’s predictions on this subset.

Experiment A: 4-gram Prediction with MLP

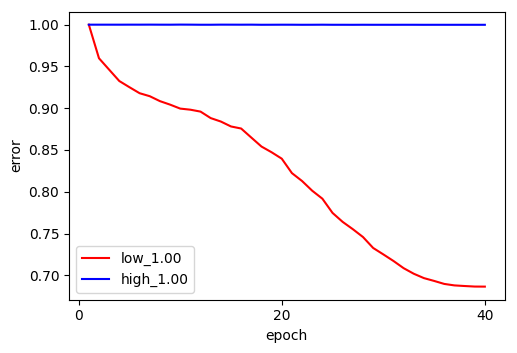

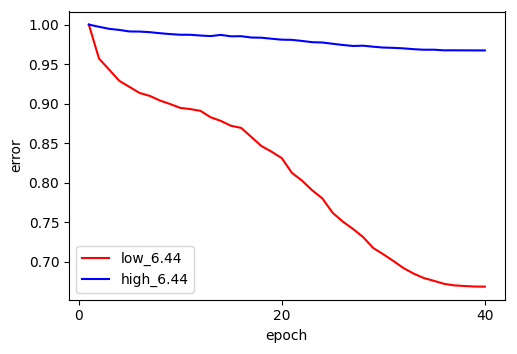

I first test Frequency Principle on a 3-layer, ReLU-activated MLP with hidden dimensions [1024, 1024, 2048].

The model is trained with 1M 4-gram built from Wikipedia dataset for 10 epochs, using the Adam optimizer. Each token is mapped to pre-trained (frozen) 300-dim GloVe embeddings, so the dimension of input is 1200. Vocabulary size is $\approx 29k$.

The results strongly support Frequency Principle. As shown in the figures, the low-frequency error (red) drops rapidly in the early epochs, while the high-frequency error (blue) remains stubbornly high and flat, across different $\delta$.

Experiment B: Extension to GPT-2

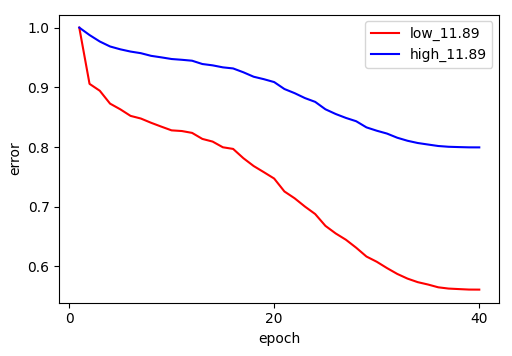

Then, I extended the experiment to a state-of-the-art architecture: GPT-2.

To maintain a static input space for the filtering method I froze the pre-trained token embedding layer (wte). All other layers (Transformer blocks, positional embeddings, LM head) were randomly re-initialized and trained from scratch. The model is trained with approximately 3M 4-grams sampled from WikiText, for 5 epochs with AdamW.

Results show that Frequency Principle persists, even in Transformers.

Conclusion

It is interesting to observe that neural networks,ranging from simple MLPs to Transformers, consistently prioritize learning simpler and smoother components of the target function. Based on these preliminary experiments, I hypothesize that the Frequency Principle is a universal property of neural networks. However, given that this study relied on several approximation methods, more rigorous investigation is required to establish conclusive evidence.

Reference

Yuan Cao, Zhiying Fang, Yue Wu, Ding-Xuan Zhou, and Quanquan Gu. Towards understanding the spectral bias of deep learning, 2020. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/1912.01198.

Tao Luo, Zheng Ma, Zhi-Qin John Xu, and Yaoyu Zhang. Theory of the frequency principle for general deep neural networks, 2019. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/1906.09235.

Zhi-Qin John Xu, Yaoyu Zhang, and Yanyang Xiao. Training behavior of deep neural network in frequency domain, 2019. URL https://arxiv.org/abs/1807.01251.

Zhi-Qin Xu, Yaoyu Zhang, Tao Luo, Yanyang Xiao, and Zheng Ma. Frequency principle: Fourier analysis sheds light on deep neural networks. Communications in Computational Physics, 28(5): 1746–1767, June 2020.